The awakening of the Industrial Revolution evoked fears of mass-unemployment by mechanical automation. In the 19th century, textile workers formed the ‘Luddite Movement’ to protest the automation of textile production. Workers damaged or destroyed machines and threatened the unravelling of social order.

Automation anxiety was also been prevalent in periods of economic stagnation. During the Great Depression, John Maynard Keynes voiced concerns on technological unemployment in his 1930 essay, ‘Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren’:1

“We are suffering, not from the rheumatics of old age, but from the growing-pains of over-rapid changes, from the painfulness of readjustment between one economic period and another. The increase of technical efficiency has been taking place faster than we can deal with the problem of labour absorption; the improvement in the standard of life has been a little too quick.”

And similar concerns have been raised during periods of rapid economic growth and industriousness. Anxieties of technological unemployment in the 1950s and 1960s were severe enough that in 1964, President Lyndon Johnson created a ‘Blue-Ribbon National Commission on Technology, Automation, and Economic Progress’.2 The purpose of the commission was to assess whether rapid productivity growth would outstrip the demand for labour. The commission found that while technological change can cause structural shifts to the types of jobs demanded, there is no evidence that it eliminates the demand for labour:3

“The basic fact is that technology eliminates jobs, not work.”

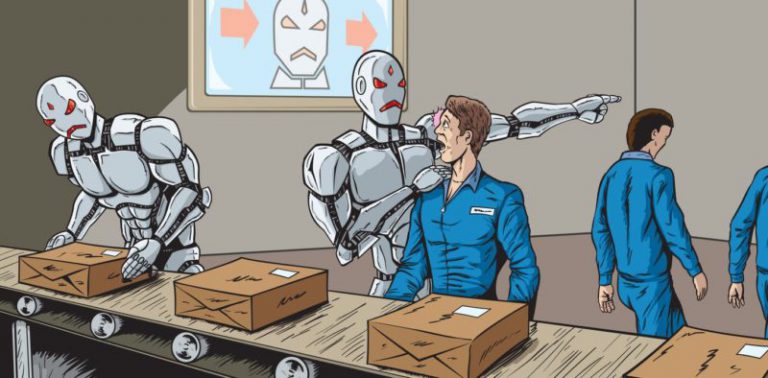

These anxieties have been a constant throughout history. It echoes back to Greek Mythology as cautioned through the ‘Promethean Myth’: Man acquires fire from the Gods; fire becomes the source of Man’s pain and suffering.4 We hear variations of the same narrative today: humans build and deploy AI; AI replaces our jobs and our purpose.5

Yet, the fears of the ‘Promethean Myth’ have been consistently unfounded.6 To take the position that ‘this time is different’ is an abnegation of economic history.

Regardless, automation anxieties have re-emerged. As AI increases the scope of capabilities that can be automated by machines, concerns abound that many labour tasks performed by humans will be replaced. In their provoking book, The Second Machine Age, scholars Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee present a troubling view of the effects of labour automation:7

“Technological progress is going to leave behind some people, perhaps even a lot of people, as it races ahead. As we’ll demonstrate, there’s never been a better time to be a worker with special skills or the right education, because these people can use technology to create and capture value. However, there’s never been a worse time to be a worker with only ‘ordinary’ skills and abilities to offer, because computers, robots, and other digital technologies are acquiring these skills and abilities at an extraordinary rate.”

It is obvious, however, that the past two centuries have not rendered human labour obsolete. Global unemployment has decreased,8 and the employment-to-population ratio steadily rose during the 20th century.9 In fact, a study performed by Deloitte found that new technologies over the past 144 years have created more jobs than they have destroyed.10

This rebuttal to automation anxiety is not to dismiss the structural challenges that AI technologies pose to labour markets. Nor is it to place a blind faith in the determinism of history. The challenges of transitioning displaced workers to meet the new labour demands created by AI are likely to be significant. Potentially as profound as the structural adjustments experienced during the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions.11

However, history suggests that the demand for labour is not the concern. Instead, the concern is the speed of transitioning displaced workers to meet new labour demands. In other words, new jobs will probably be created by AI, but transitioning people to a future of work defined by AI could be problematic. At least in the short-term.

- John Maynard Keynes. 1930. “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren” in Essays in Persuasion (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1932), 358-373.

- “Lyndon B. Johnson: Remarks Upon Signing Bill Creating the National Commission on Technology, Automation, and Economic Progress.” n.d. Accessed October 2, 2018. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=26449.

- Bowen, Harold R. (Chairman). 1966. “Report of the National Commission on Technology, Automation, and Economic Progress: Volume I.” Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- “PROMETHEUS – Greek Titan God of Forethought, Creator of Mankind.” n.d. Accessed October 2, 2018. http://www.theoi.com/Titan/TitanPrometheus.html.

- Harari, Yuval Noah. 2017. Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow. VINTAGE ARROW – MASS MARKET.

- Autor, David H. 2015. “Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives: A Journal of the American Economic Association 29 (3): 3–30. pg. 3-5; Mokyr, Joel, Chris Vickers, and Nicolas L. Ziebarth. 2015. “The History of Technological Anxiety and the Future of Economic Growth: Is This Time Different?” The Journal of Economic Perspectives: A Journal of the American Economic Association 29 (3): 31–50.

- Brynjolfsson, Erik, and Andrew McAfee. 2016. The Second Machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. 1 edition. W. W. Norton & Company. pg. 11.

- “Unemployment, Total (% of Total Labor Force) (modeled ILO Estimate) | Data.” n.d. Accessed October 2, 2018. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/sl.uem.totl.zs.

- Autor, David H. 2015. “Why Are There Still So Many Jobs? The History and Future of Workplace Automation.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives: A Journal of the American Economic Association 29 (3): 3–30. pg. 4.

- Stewart, Ian, Debapratim De, and Alex Cole. 2015. “Technology and People: The Great Job-Creating Machine.” Deloitte. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/finance/deloitte-uk-technology-and-people.pdf.

- Brynjolfsson, Erik, Daniel Rock, and Chad Syverson. 2018. “Artificial Intelligence and the Modern Productivity Paradox: A Clash of Expectations and Statistics.” In The Economics of Artificial Intelligence: An Agenda. University of Chicago Press.